Jacob Greene was a sweet boy raised by a loving, tight-knit family… of cultists. He always obeyed, and was so trusted by them that he was the one they sent out on their monthly supply run (food, medicine, pig fetuses, etc.).

Finding himself betrayed by them, he flees the family’s sequestered compound and enters the true unknown: college in New York City. It’s a very foreign place, the normal world and St. Mark’s University. But Jacob’s looking for a purpose in life, a way to understand people, and a future that breaks from his less-than-perfect past.

When his estranged sister arrives in town to kick off the apocalypse, Jacob realizes that if he doesn’t gather allies and stop the family’s prophecy of destruction from coming true, nobody else will…

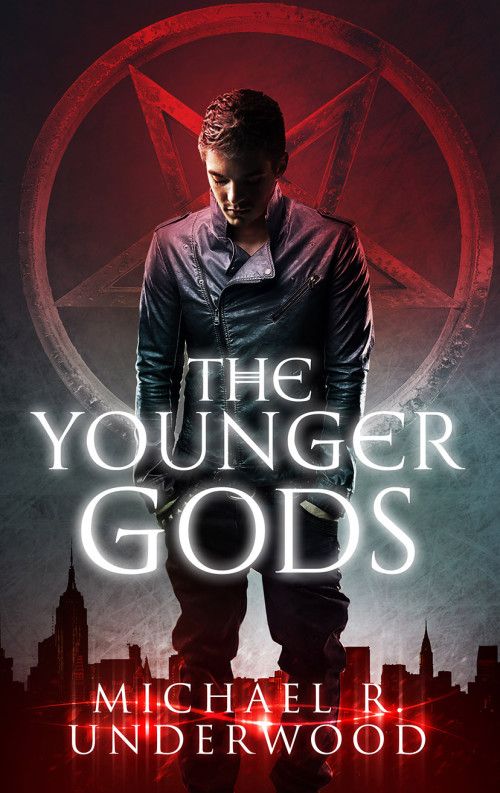

![]() The Younger Gods, available October 13th from Simon and Schuster, is the start of a new series from author Michael R. Underwood. Read an excerpt below!

The Younger Gods, available October 13th from Simon and Schuster, is the start of a new series from author Michael R. Underwood. Read an excerpt below!

CHAPTER ONE

I expected many things after I left my family: the loneliness of being separated from my roots, serious financial hardship, and drastically fewer blood sacrifices with dinner.

But I did not expect the discouraging reality of having to count on strangers.

Sitting in the main room of the St. Mark’s University library, I watched hundreds of my fellow students at work. They hunched over laptops, poured through stacks of books, and argued points of rhetoric, trying to assemble arguments for term papers. There was so much life all around me, so many people. It was invigorating, if a little claustrophobic.

And though I was among them, I was still apart, since unfortunately, none of these people were my assigned partners for the sociology project. I arrived thirty minutes early to claim a table, wore a distinctive orange jacket, and stood every minute to look around, ready to signal them across the crowded room.

And yet, they did not come. It was now more than forty minutes after the time I had set.

One woman joined three others who had been browsing Facebook on the university computers since I arrived, and then the group approached my table. One of the Facebook devotees looked down at the table, then said, “Can we sit here?”

“I’m very sorry. I’ve reserved this table for a group project. My group should be arriving presently.”

She shifted her weight, arms crossed. “Except you’ve been at that table for like an hour, and no one is here. We have work to do too.”

Oh, really? I locked my eyes on the young woman and leaned forward. “Work so pressing that you’ve spent your time diligently playing farming games on Facebook? Is that why you’re here at this university, to major in reciprocal guiltand gift-driven computer games? Even if that were so, I have reserved the table, and I’m afraid you will have to look elsewhere. Good evening.”

“Who the fuck are you?” the woman asked.

“My name is Jacob Hicks.”

“That was a rhetorical question.” The woman scoffed, then looked to her friends. The newcomer shrugged, then pointed to a table across the room.

The group left, and over my shoulder, I heard someone utter “Asshole.”

I sighed, and checked my watch again: 7:39. I’d confirmed for 7 PM, and had received no messages from any group members explaining their tardiness or suggesting alternative plans.

Without the group, I would have to complete the project by myself, in a way that appeared to be the work of a group. Anything but the highest marks would be unacceptable, as I was already shouldering a substantial debt in order to secure a degree and enter the non-magical workforce, to put my old life behind me. Each additional semester of tuition would take years of effectively-garnished wages to pay off, which was far from acceptable given how I might need to move frequently to avoid my family.

Behind me, a group of students broke their blissful silence and started to talk.

“I hate it. My parents are making me fly home for Christmas, and I don’t even want to go, because I could stay here and go skate at Rockefeller Center with Julio and shop at Saks. All we have at home is crappy strip malls. And my crazy grandma will just spend the whole time drunk and making racist jokes.”

A male voice joined the rant. “Right? My parents are so lame. They say that I have to come home because they already bought the ticket. It’s the same passive-aggressive shit. ‘We’re paying for your school, so you have to do what we say.’ ”

And on they went. Listening to other students complain about their families was revelatory. It seemed that hurt feelings, oppressive expectations, and lies of omission were not limited to my own family. It was consoling, in its own small way. A tiny patch of common ground.

Rather than continuing to stew in my discontent and lash out at others (even if they deserved it), I gathered up my texts, returned them to my bag, put on my coat, and snatched up the overpriced tea I’d acquired from the ubiquitous Starbucks.

As soon as I stood, other students swept down on the table, taking seats like a murder of ravens pouncing on a stray crust. Would that they had more success in their studying that night than I.

Leaving the library, I was again assaulted by the cacophonous noises and panoply of smells that were New York. Queens comprised a far more subdued version of the city’s overwhelming stimuli, but within a moment, I saw airplanes arcing overhead, cars trundling by, the smell of rotted paper and garbage, and the fullness of hundreds of heavily bundled bodies as students hurried about the campus. They were entirely apart from the life I’d known.

People here did not live in preparation for prophecies about the coming of the end, did not strike bargain after bargain with beings that lived at the center of the earth, did not challenge one another for primacy within the family. They had their own petty and beautiful lives, and they had to be protected so that humanity could be nourished.

My dormitory was only a five-minute walk from the library, one of the primary reasons I’d selected it on my Residence Life application.

Upon reaching the door to my room in the dormitory, I rattled my keys loudly to signal my return to my roommate, Carter. He seemed to ignore knocking, but the distinctive jingle of keys proved more telling. I heard no protest, no scrambling or shushing, so I was confident that I could open the door and step inside.

The dormitory room was, in total, larger than my last room at home, and I had to share it with only one person rather than my two brothers. But as I was learning, sharing a room with a stranger was a far sight from sharing with family.

Carter and I had elected to loft each of our beds, reducing overall space but giving us each more to ourselves, which was necessary both for his libido and for my sanity.

The divide in the room could not have been clearer. My walls and shelves were nearly empty. A small stack of books sat on my desk next to a miniature refrigerator and the half-dresser. I’d only left home with one bag, and the student loans I’d taken would not go very far if I planned for them to cover all of my expenses, even with my part-time work. As a result, my pocket money was nonexistent. Every time I spent money outside my meal plan, I’d have to make it up somewhere else.

By contrast, Carter’s portion of the room was covered in posters from films and sketched portraits of impossiblyproportioned women clad in outfits that would be considered risqué at a bacchanal. He had stacks and stacks of comics, films, and games. Furthermore, he had filled the communal closet with sporting equipment I’d never seen him use, heaping bags and boxes worth. And the one time I’d opened the closet to invite him to organize it to allow me some space, he’d shouted me down and slammed the closet closed.

For once, it seemed that Carter did not have company. He sat at the under-the-loft desk, his attention split between a computer screen and a television.

Carter’s family lived upstate, in Buffalo, and he had little sense of the value of money. Which was good in that he was generous without trying, but bad in that he saw everything as disposable. Everything had a price and it could be replaced. It seemed to have nothing to do with being Indian and everything to do with being rich enough to not have to care.

“Hey, Hicks,” he said, not looking away from his screen. I had assumed a pseudonym upon arriving in New York to conceal my movements from my family. I had made the logistics of creating an academic and personal record complicated, but I now had a completely new life as Jacob Hicks.

The television screen illuminated Carter’s golden-hued skin, light for a south Asian. In North Dakota, there had been nearly no people of color, so I found myself quite overwhelmed by the diversity in New York City, living among millions of people from all around the world. Several stern talking-tos later, I made a concerted effort to learn the basics of identifying different ethnic heritages so that I might not give offense through such mistakes as intimating that a Chinese woman was Japanese, when her grandparents had been killed by the Japanese during their occupation of Manchuria. The sting of her slap had faded shortly; the realization of the pain I’d caused her did not.

With sun-kissed skin and lean muscle, Carter was extremely popular with the women on our floor and beyond, while I, with a lanky frame and a complexion that approached that of chalk, was often asked if I was under the weather.

“Hello.” I gestured at his screen. “Is that another episode of your bathetic seemingly interchangeable formulaic crap?”

A beat.

“Yeah. Are you still a freak?”

“So it would seem.”

That seemed to satisfy him. I unpacked my bag onto my desk and booted up my laptop.

We’d used computers at home, but I quickly discovered that technology changes far faster than Father had ever bothered keeping up with. Apparently, a 486 was no longer considered worthy of the task of engaging with the world at large.

Luckily, the university retained an array of staff to consult on technical matters. It had taken all of a Saturday afternoon with a tremendously patient young woman named Audra, but after that, I was able to use the laptop for all of the basic processes required as a student.

Seeing no email from any of my classmates explaining their absence, I drafted a polite but insistent message inquiring after each of them.

A few minutes later, Carter said, “Oh yeah. Some people called for you a while back, said they couldn’t make the meeting or something. They thought I was you at first, though they were calling a cell.” He shook his head, dismissing the notion.

Well, that solved the mystery of the group’s truancy, if unsatisfactorily. They had taken the number provided as a personal cell and therefore expected to speak with me when calling the dormitory phone.

“I’m going to have some company over in a bit, if you don’t mind.” He would have company over even if I did mind, as I discovered one night when I needed to study for a mid-term in sociology. It did not take long for me to excuse myself once the panting started.

There would likely be people in the common room, and I’d learned to read anywhere, anytime, no matter how many screaming siblings, spectral howls, or ritual chants filled the house.

“Of course. Will your libido be sated by eleven, perhaps? Tomorrow is Tuesday.” My eight fifteen AM class was on Tuesdays and Thursdays, which meant I was up at half past six.

Carter grinned. “Sated? No. But I’ll probably have gotten sick of her by then.”

“How charming,” I said.

I packed up my laptop again, along with several course texts, and made for the common room.

Four of my floormates were playing cards at the table, and another was splayed out on a couch, watching television. I gave her ample space and settled at another couch, resuming my work. I’d transferred into a more advanced chemistry section once I discovered just how rudimentary their 101-level material truly was.

You can say many things about my parents’ choices and teaching methods, but our education was incomparable. Even as a freshman, I was taking advanced science courses in order to stay engaged. In fact, that knowledge had given me one of my very few advantages in making connections in the city.

Tessane, one of my floormates, nodded as I sat down. “You have time to help me with this anatomy quiz?” she asked, holding up a partially-colored page showing the cardiovascular system.

“Certainly,” I said, setting my own work aside.

Bodies. Bodies made sense. Biology was a system, complex but understandable. Everything working in concert. And it felt good to speak from confidence. Tessane was one of the only people in New York who had welcomed me into her world without question. We worked together in the library, one of the many ways that I had conspired to be able to afford this college tuition. Tessane was kind to me, and rendering assistance on anatomy was the least I could do to repay her. She was a first-generation college student, her family recent immigrants from the Philippines. And she was quite stunning, though I did my best to ignore that fact, as she’d given no indications of any interest, and I did not have so many friends I could afford offending one by making a fool of myself with an expression of romantic intent.

Five minutes into helping Tessane review pulmonary function and doing my best to ignore how close she was sitting, someone turned up the television.

“This is a breaking news update from KRTV3,” said a disembodied voice. “We interrupt your regular broadcast to bring you the breaking news of a murder in Central Park.”

I looked up from Tessane’s text to the television. A blandly handsome man sat at a news desk, immaculately dressed, his hair so firmly done it might as well have been the plastic that made up my sister’s Frankensteinian dolls, bodies sheared apart and glued back together to fit her vision of proper beauty.

The screen showed Central Park, lit by streetlamps. Police had erected a circular cordon around a tree, which was covered in shadow.

“A runner identified a body crucified on a tree, with a knot work design carved above the victim’s head. The grass in a ten-foot circle around the tree appears to have been burned to ashes…”

I leaned forward, a wrenching familiarity clamping down on my gut.

Please, no. Not here.

The television switched back to the news anchor.

“Details are still emerging, but certain sources report that this crime may have occult motivations, and could be tied to a cult group.”

Not just any cult.

I couldn’t be sure without a closer look, one that the channel seemed unable to grant due to police procedure, but the carved symbol, the way the body hung, the patch of dead grass…

I had to know for sure. If they’d come here, now, it could only mean one thing:

My family had caught up with me.

CHAPTER TWO

My sister was likely less than an hour’s subway ride away, perhaps ready to kill again, but getting to her would be no small feat.

In addition to the extensive police presence, even if I was able to go and confirm the nature of the killing at the park, I wouldn’t be home until after midnight, thanks to the slowed rate of subway service and the planned change that would require me to take the train past my own stop and then turn back around at the line’s terminus.

I decided to wait for more details. Maybe it was just a coincidence, a similar ritual used by another group or a deranged loner who had stumbled upon the wrong text.

With my mind racing through possibilities and implications, tracing out a decision tree filled with corrupted branches of terrifying results, I continued to work with Tessane, though poorly, my lack of focus leading me to read the parasympathetic nervous system as the sympathetic nervous system.

A few minutes later, I reclaimed my focus. I could either help Tessane or I could spin my wheels in worry to no effect. I chose to make a difference.

“So, you must have had one hell of a biology teacher in high school?” Tessane asked.

“I was homeschooled. My parents were very thorough,” I said, my mind flashing back to memories of lashings when I took a misstep in logic, beatings each time I misspoke the Enochian incantation for a weekly sacrifice. In the Greene household, failure led to pain, pain led to learning, and learning kept the switch at bay.

In another joke the universe had at my expense, Carter was not done at eleven, or eleven thirty. With luck, I might have actually been able to make it to the park and back by the time the sock vanished from the door, which left me somewhat glad to have been able to help Tessane but entirely unsettled by the need to resolve this uncertainty.

I tried to get my own work done, but it was useless. I even resorted to reading the mass culture magazines left in the common room, but even the vapidity of celebrity life could not distract me. I doubt anything less than a freshly-unearthed ritual text informing me how to cut off the family’s access to the power of the Deeps could have held my attention.

But when I finally got to my bed, sleep came quickly, as if the darkness were eager to take me once more.

I knew they would come, but I still was not prepared for the nightmares. Perhaps I will never be.

It was the night of the senior prom.

The edges of the world were vague, as if sketched in with a shaky hand. It started, as always, at my friend Thomas’s house, when I arrived in the lamentable feces-brown family truck.

Thomas Sandusky was my best and only friend back home. On my sixteenth birthday, I was entrusted with the task of securing supplies we could not provide for ourselves. Thomas was the general store owner’s son in the closest town to the family compound. Over the first few months, we progressed from the apathetic invisibility of strangers to the neutral nods of greeting to deeper conversation.

A year later, we’d become fast friends, the only bit of the real world I’d been allowed. And so, when Thomas asked me to come out to his senior prom so we could hang out as friends, I leapt at the opportunity. That my parents excitedly agreed to an event that would expose me to more of the corrupting influences of the world should have been my first warning sign.

My tuxedo was rented, and it fit as comfortably as a hair shirt used for torture. The cost of the night nearly wiped out my savings, but Thomas had impressed upon me the need for formality if we were to have a chance of attracting the attention of any of the girls. Thomas opened the door, wearing his own tuxedo, though his looked like it was made for him. Where I was sallow and gaunt, Thomas was build broad and tanned from working summers on his uncle’s farm.

“Looking good, man!” he said, thudding down the front steps of the farm house and grabbing one hand, wrapping me up in a burly hug. His smile lit up any room he was in,, would have lit up an entire town. I cannot imagine how much light he could have brought into the world, if not for me.

In an instant, a masque of pain was superimposed over his smile, banishing the happy sight as the memories overlapped. I heard him scream, that scream that I will never be able to put out of my mind, no matter how long I live, nor how many other memories I pile into my mind. Her pain has been seared into my mind’s eye, a brand of shame to carry always.

Then I was out front of his house again, listening as he rattled off descriptions of the various gorgeous and single women that would be there at the prom.

Then we were at dinner, and Thomas told me about the college he was going to in the fall, the college he will never see again, because of me.

Thomas talked circles around me; he was the sort who could not abide a silence longer than a split second, he’d fill the air with speculations and odd observations and companionable chatter. We went together well, as I was just happy to listen, to take from him morsels of knowledge about the outer world. My parents had raised me to scorn the outer world, to see them as lesser beings, ignorant lambs who would come dumbly to the slaughter when the appointed time arrived.

I’d learned by then what topics outsiders saw differently, which left me tremendously little to speak of that would be of interest, given that outsiders saw little artistry in divinatory vivisection of vermin and did not believe the lore of the gods, their succession, and the Gatekeepers. Until Thomas brought up biology again, leaving me an in to dive into an obscure bit of scientific history.

Thomas was supposed to become a scientist, discover unknown truths more tightly protected by science than the Gatekeepers guarding the primordial cage wrought to trap the Younger Gods.

Every moment built the dread, every word on the drive to his school brought us closer to the end, and there was nothing I could do to change it. I was locked into the memories, a helpless voyeur in my own history, strapped to the chair in room 101, my mental eyes forced open.

The prom unfolded in snapshots, a montage of moments, from spilling punch on my tux when jostled by a wildly gesticulating classmate of Thomas to the flush of attraction as she dabbed the stain, her hand warm, soft. The supreme selfconsciousness of trying to dance with Ilise, the gesticulator, and then fleeing off to the corner, with Thomas trying to drag me back out for another round of socialization.

But the crowds, they were too much. Too many people, too chaotic, too loud.

We met halfway with me squatting at a table while Thomas cheerily made his best attempts to impress the girls he’d spoken about all year, trying to create a big moment,

“Like the movies,” he said. Everything was movies and TV and games for Thomas, like he was speaking a whole different language. He’d learned to stop expecting me to know any of them, but continued to speak of him.

But life was not a film, and despite his best efforts, no doubt thanks to my discomforting presence, by the end of the night when the slow dances and barely-constrained groping were finished, coupes and cliques moving off to their after-parties, Thomas and I were left to return to my house, where father had asked to meet this friend of mine who I spoke so cheerily about.

Thomas was welcomed by my whole family, everyone dressed in their Saturday best. After a short inquisition about his family background, blood type, and astrological disposition, I managed to escape to my room so we could wind down the night before he headed home. I

We reviewed the night, laughed at our failures, and once more I listened to Thomas and his speculations, his intricate analyses of the tiniest of gestures, the turns of phrase this or that girl had used and what that meant for his chances, who was heading to which college, and so on. He wrapped up the whole night into a story, summarizing the culmination of his life, ready to face the ritual with pride, as my parents said he would. My parents waited outside, preparing for the ritual. I was a fool, but how was I to know?

Thomas slipped into a light doze in my brother Saul’s bed, and my father crept into the room, his silence a prayer to the Onyx Lord of the Seventh Gate, chief among our Gatekeeper patrons.

Father bore the ritual dagger, the blade that had been in our family for millennia. It was the symbol of our role in the coming of the Last Age, the centerpiece of every holiday, every blessing, and the crux of our connection to the Gatekeepers.

Thomas’s eyes were closed, his brow shining after an exerting night of nerves and excitement.. My heart beamed with pride, that my friend had so boldly volunteered to be a page to the Onyx Lord, to join the service of our patron.

But he hadn’t. I just didn’t know. I’d been lied to again, like I’d been lied to my whole life.

My father raised the dagger, and Thomas opened his eyes, with the satisfied sigh of a evening well-spent. Then he saw the knife, and everything changed.

He screamed, eyes going wide, bright eyes that were meant for laughter, not terror. Why should he be afraid? There was no reason.

This was supposed be a happy time. The other sacrifices had come willingly, joyfully, their eyes soft, bodies wavering in turn with the rhythm of creation.

Thomas reached up and swatted my father’s hand away, screaming “What the hell!” again and again.

“What’s wrong?” I asked. He was a volunteer, and his heart had to be harvested so he could be delivered to our patron and master. My father had explained everything to me when Thomas asked about the prom.

“Why the hell does your dad have a knife?!” he said, clawing free of the bed, seeking refuge from my father, who moved without alarm, a serene smile on his face.

“Do not worry, my child. You’re going to a better place,” Father said.

Thomas grabbed my arm, moving behind me as I sat up in bed. “What the hell, Jake!”

“Don’t you know?”

I looked at my father, scales of self-delusion falling from my eyes, though I didn’t know that at the time. For me, it felt as if the whole world was falling apart.

“You said he knew!” I shouted, matching Thomas’s panicked tone. “You said that he was volunteering!”

My father never lied to me. Our sacrifices chose their fate, every one of them. That’s how it worked. They chose it.

I sat up to interpose myself, looking to my father. He took a long breath, just as he did any time he had to explain something to me more than he cared to (which was any time after the first).

“He has volunteered for the joining. You said as much.”

Thomas grabbed a lantern and wielded it like a club, trying to keep my father at bay. “The hell I did. I’m getting out of here!”

It was all wrong.

I raised my hand toward the knife, trying to stay my father’s hand. “He has to be willing. We need to let him go, it won’t work if he’s not willing!”

My father looked at me, his eyes empty. “Silence,” he said in Enochian, the First Tongue. He turned his hand and made the signs of communion, tapping into the Deeps. The dagger leveled at my throat, an unseen force slammed me against my dresser and held me fast. I strained against the binding, but it was useless.

I tried to close my eyes, to shut it all out, to disbelieve how much my world had disintegrated. But the working held my eyes open. He made me watch.

My father flicked his hand again and Thomas was caught in the binding. I smelled sulfur as the binding pulled him to the floor and forced him prone.

The rest of the family came in to witness the ceremony as he screamed. Esther and Joseph; my mother, Joanna; even little Naamah and Saul. They watched with ice-cold faces. Why didn’t they see that this was wrong? That Mother and Father had lied to us all along?

When we were all in place, he raised the knife and called out to the Onyx Lord.

“Take this gift, Keeper of the Seventh Gate. Grant us your favor as we watch and await the birth of the Younger Gods.”

He completed the ritual as I tore at the binding with my will, grasping at the knotting of power that held me back. But Father was the scion of the Greenes, chosen vessel of communion, and I had no more chance of breaking his binding than a cub has of felling a lion.

When it was over, Father released me, and Mother helped me up and wrapped her arms around me as I cried.

It was then that I knew I had to leave. They were my family, but I didn’t belong there anymore. These were the people who lied to me, tricked me into bringing Thomas here, my only friend, who killed him while I watched. He was not a volunteer; he was a victim. And I was their patsy.

The Younder Gods © Michael R. Underwood, 2014